Considering Muni Bonds

Municipal bonds are a sometimes overlooked corner of the bond market, but for some investors they may be a place to find real opportunities.

The Basics — Municipal bonds (Munis) are bonds issued by states, local governments or other public entities. Two main types of muni bonds are GO (general obligation) and Revenue bonds, depending on whether the principal and interest payments are secured by the taxing authority of the issuer or by the revenues of a public project. The advantage to investors is that the interest paid by a municipal bond is generally exempt from federal taxes.

- TIP #1 — Investors buying bonds issued in their state of residence may have the income exempt from their state taxes as well.

- TIP #2 — Some higher earning investors may be subject to the alternative minimum tax (AMT), and need to be sure to avoid muni bonds that may be included in the AMT calculation.

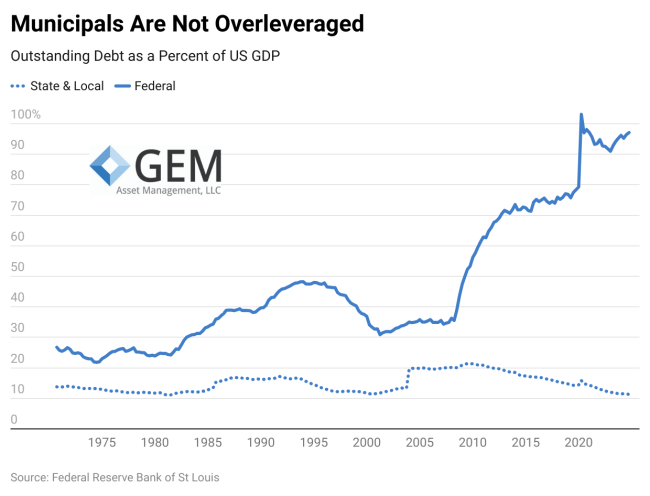

Grand scope — Because their interest is not taxed, muni bond issuers pay a lower rate which on an after-tax-basis can be equivalent to, or better than, other taxable bonds. This is a benefit that allows these public entities to keep their borrowing costs lower. However, we find that state and local governments are generally not over-leveraged. The high level of federal debt relative to the size of the economy has caused some concern in the market for US Treasuries.

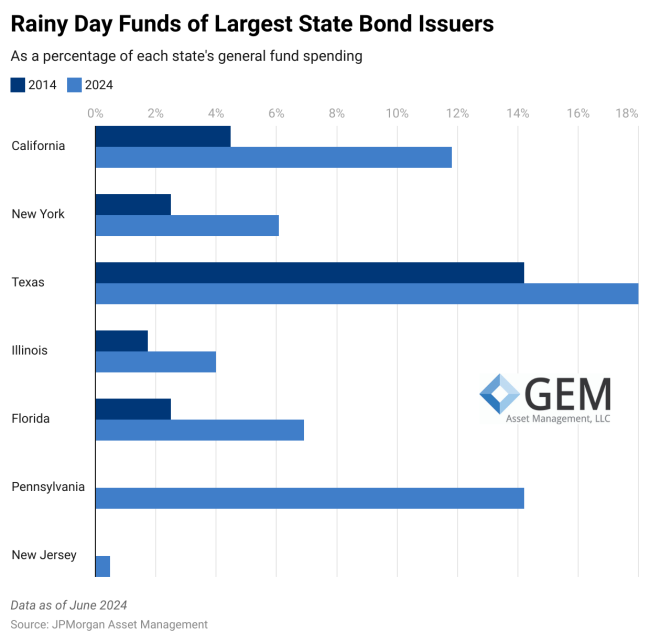

Reduced Risk — Not only do municipalities not look to be overburdened with debt, but many have improved their quality in recent years by financing at lower interest rates and taking the opportunity to build up “rainy day” funds.

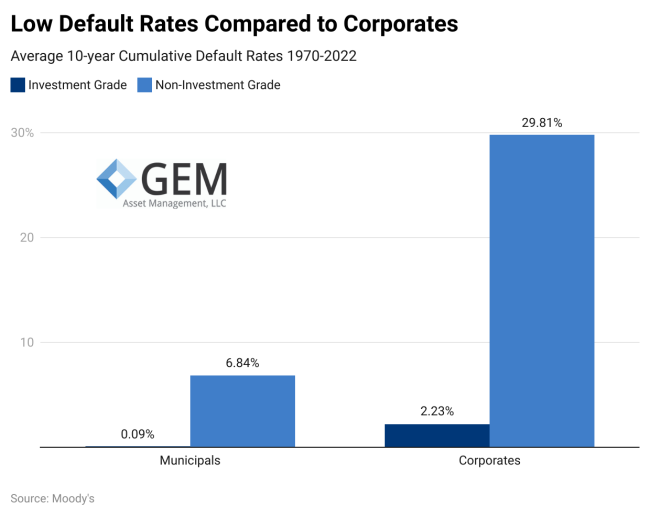

More Assurance — The strengthened financial positions of many of these issuers only bolsters what has been a low default rate for municipal bonds.

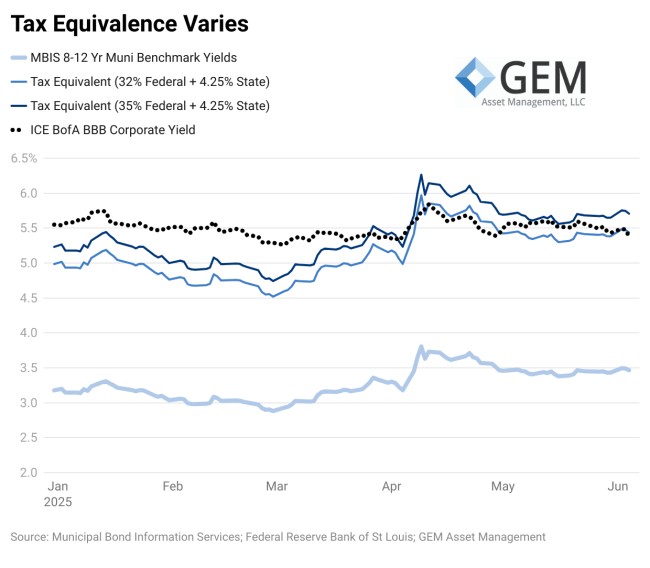

Looking deeper — They don’t make sense for everyone. Sure, municipals have an attractive risk-reward profile, but the tax advantages are worth more to those who pay more in taxes. As a result, muni bonds are bid to a price where their yields are roughly comparable to corporate bond yields for taxpayers in the higher tax brackets.

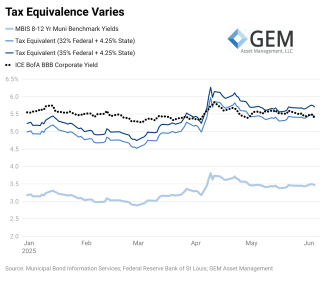

How it works — Investors need to compute what taxable interest rate would give the same yield after paying the appropriate taxes.

- For example, after paying 35% taxes a corporate bond yielding 6.15% would be equivalent to a municipal bond paying 4.0%.

In the chart above we looked at rates using the 32% and 35% federal rates in addition to the 4.25% Michigan state tax. At times, the taxable rate is better while other times the tax-free rate is best.

All bond investments should be evaluated in the moment against comparable alternatives. Variances can occur for different credit qualities and maturity lengths of the bonds.